As I write this column on April 23, 2021, the U.S. is in the eleventh day of its “pause” in vaccinating Americans with the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. The U.S. pause came on the heels of several weeks of similar disruptions in the European rollout of a different COVID-19 vaccine, manufactured by AstraZeneca and not authorized for use in the U.S.

The reason for both pauses: a potentially fatal clotting disorder that strikes a tiny percentage of people vaccinated with those two vaccines.

Hours ago the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to recommend ending the pause, with no restrictions but new warning language about the clots. Almost immediately government regulators accepted the recommendation. J&J vaccinations will resume in the U.S. just as soon as the logistics are under control, probably before I manage to get this column finished and posted.

This column is about the COVID-19 vaccine blood clots – and why I think the pauses were a bad risk communication decision that is likely to exacerbate vaccine hesitancy and damage pandemic response. But first some basics.

Vaccine side effects

Like nearly all medications, vaccines have side effects. The common ones are identified in studies on volunteers, but the rare ones don’t show up until after the vaccine is released. Almost by definition, the common side effects are mild, an aching arm or a brief bout of fever; if they’re severe, the vaccine probably won’t get approved for release. But the rare side effects, the ones you don’t find until millions of people have been vaccinated, might be deadly.

The first such rare, severe side effect in COVID-19 vaccines materialized recently – so far not in all of them, but only in the two manufactured (using a similar technology) by AstraZeneca (AZ) and Johnson & Johnson (J&J). It’s a strange and potentially deadly sort of blood clot, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, accompanied by abnormally low platelets – CVST with thrombocytopenia. (The emerging shorthand for this mouthful is “thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome” or TTS – but I’m sticking with “CVST” for the rest of this column.) CVST is rare even if you get one of those two vaccines. It’s significantly rarer if you don’t – unless you get infected with the virus: COVID-19 itself causes more CVST than any vaccine, plus, of course, all its more common potentially deadly dangers.

On a population basis, the medical implications of vaccine-related CVST are minor. But its psychological and therefore its policy implications are huge. The risk communication dilemma: What should officials do about the gap between the two?

Bear in mind that vaccine side effects are assessed by a different standard than the side effects of other medicines. Imagine a medicine that’s 100% effective in curing a disease, and a vaccine that’s 100% effective in preventing that disease. For the medicine to be worth taking, its side effects only have to be less dangerous than the disease. But the vaccine is meant to be taken by healthy people who don’t have the disease and might never catch it whether they’re vaccinated or not. So it’s not good enough for the vaccine to be less dangerous than the disease it prevents; it has to be less dangerous than going unvaccinated and taking your chances of possibly getting the disease.

The psychological distinction between vaccines and other medicines is much bigger than this medical distinction. When you’re sick, the downsides of your disease are vivid in your mind; you’re living with them. So you may pay too little attention to your doctor’s warnings about the risks of the medicine she’s prescribing. When you’re healthy, on the other hand, it feels profoundly counterintuitive to take a medicine that poses any risks at all. Voluntarily exposing yourself to vaccine side effects is a proactive decision, a sin of commission; if the vaccine does you harm, that’s on you. Going unvaccinated may be statistically much riskier, but that’s merely a sin of omission; even if you get sick, at least you didn’t get sick because of something you did on purpose.

Vaccines, moreover, are based one way or another on the pathogen they’re designed to fight. They work by convincing your immune system that they are the pathogen, tricking it into developing antibodies that will then be available to fight off the pathogen if the need arises. That feels counterintuitive too: to voluntarily let yourself be injected with a weakened or dead or bioengineered version of some disease. So vaccines are a tough sell.

They’re an especially tough sell when the disease they prevent isn’t widespread. Consider the paradox of the measles vaccine in places without much circulating measles. Getting the shot poses only a tiny risk. But assuming absolutely nobody in your vicinity is infected with measles, not getting the shot poses an even tinier risk. The paradox: If everybody reasons this way and decides not to get vaccinated, measles will come roaring back. By the time being unvaccinated becomes obviously much more dangerous than being vaccinated, it might be too late to get vaccinated. So getting vaccinated against measles makes medical sense even if measles isn’t a sizable risk where you live, because measles will soon be a sizable risk where you live unless most people get vaccinated.

Of course in places where measles is circulating already, the medical case for measles vaccination is simpler. In most of the world right now, COVID-19 is circulating already, so the medical case (the risk-versus-benefit case) for COVID-19 vaccination is simple. A rare side effect doesn’t change that. Even if you are young and healthy, your risk of catching the virus and having a severe or long-lasting case of COVID-19 is higher than the risk from the vaccine. If you’re a middle-aged or older adult in a place where COVID-19 is circulating, and you’re not staying home so you can’t get infected, your risk from even a few extra unvaccinated days is roughly comparable to your CVST risk if you roll up your sleeve for the AZ or J&J vaccine. A few unvaccinated weeks or months are almost surely riskier than getting one of these two vaccines.

More than three million people have died from COVID-19 so far. Hundreds of millions have caught it. Billions are desperate for the chance to roll up their sleeves for any vaccine.

But the psychological case for vaccination is never simple. Somewhat fewer billions, but still billions, are reluctant to roll up their sleeves, or even determined not to. Fear of vaccine side effects is one of the main reasons why. News of a severe vaccine side effect exacerbates that fear. Official decisions to “pause” vaccination rollouts in deference to that side effect further exacerbates the fear – no matter how often officials say the pause should reassure people that the system is working.

Vaccine hesitancy

The vaccine-related CVST clots are turning up mostly in women under 50. COVID-19 is most dangerous to the elderly. So are young women better off going unvaccinated than accepting the AZ or J&J vaccine? Conceivably so, if they live in a place where very little COVID-19 is circulating, or if they’re extremely cautious about staying home and taking all the recommended precautions when they go out, or if they can get one of the other vaccines with only a short delay. Definitely not, if they face a nontrivial risk of catching COVID-19 and no other vaccine will be available to them for months.

For most people in most of the world, getting any COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible is the medically sensible thing to do, and the miniscule clot risk of some vaccines doesn’t change that. Anything that discourages people from getting any vaccine or discourages governments from deploying any vaccine is bad for individual health, bad for public health, and bad for pandemic control.

Sure, if people or governments have a choice, some COVID-19 vaccines are preferable to others – because they work better, last longer, cost less, were studied more carefully, are easier to administer, have fewer serious side effects, etc. The biggest competitive advantage of the AZ vaccine is its low cost; the biggest competitive advantage of the J&J vaccine is its one-dose protocol. The biggest competitive advantage of them both is that they don’t require extremely cold freezers, which makes them easier to distribute, store, and administer. Now they both have a newly discovered competitive disadvantage: CVST. But the differences among the vaccines are far smaller than the difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated. All the vaccines (at least all the vaccines developed in the U.S. and Europe) are hugely preferable to no vaccine.

By far the main effect of the COVID-19 vaccine controversy over CVST clots is the controversy, not the clots. The clots are hurting small numbers of people. No doubt there have been more CVST cases than they’ve found so far, and there will be more to come if the vaccines continue to be used. But we’re still talking at most about hundreds of cases and dozens of deaths – not millions or even thousands. The controversy will almost certainly hurt many more people by exacerbating vaccine hesitancy – especially hesitancy about the AZ and J&J vaccines, of course, but potentially hesitancy about all COVID-19 vaccines, or even all vaccines period. This increased hesitancy will do modest damage in the U.S., which has ample supplies of other vaccines with no known clot problems. But even in the U.S., the populations targeted for the one-dose J&J vaccine – the homeless, the homebound, etc. – may not be so readily reachable with those other, two-dose vaccines. It will do more sizable damage in Europe, which is currently pretty dependent on the clot-causing AZ vaccine.

The increased hesitancy is potentially disastrous for developing countries. The vaccines that have CVST problems are also cheaper and easier to administer than the ones with no such problems so far. They were expected to be the workhorse vaccines for the developing world. If the developing world’s people or governments turn against these vaccines, the prospects for managing and ending the pandemic will dim. Opinions differ on the extent to which ongoing COVID-19 spread elsewhere in the world threatens us all. It certainly threatens the countries whose people lack access to a vaccine they’re willing to take.

The best way to handle the clot controversy, therefore, is whatever way (or at least whatever honorable way) will minimize how much the controversy undermines vaccine confidence.

What are – or were – the options? I see three:

Secrecy. I think officials deserve credit for not attempting this option.

Pause. This is the option they picked, and I want to focus most of this column on why I think it was a mistake.

Informed consent. This is the option they are belatedly working toward. I wish they’d picked it at the outset. In fact, I wish they’d picked it before the outset – informed the public before rolling out the vaccines that rare side effects might well materialize, might possibly require changes in recommendations, and wouldn’t interfere with the rollout.

I’ll take them in that order.

1. Secrecy.

Secrecy is always either the best (though repulsive) or worst way to cope with bad news. When secrecy works, the bad news stays permanently secret and thus does zero harm. The clots would still do harm, of course, but not the controversy, for there would be no controversy. But when secrecy fails, the results are often catastrophic. People who belatedly learn they were secretly endangered end up overestimating the danger, sometimes by orders of magnitude. Worse, they lose trust in the technology about which they were misled (in this case vaccination) and the institution that misled them (public health).

Imagine you’re an expert who believes a particular risk is tiny, believes the public is likely to overreact to that risk if they learn about it, and believes the overreaction will do far more harm than the risk itself. If you think you can get away with it, it’s obviously tempting to keep the risk secret. Total secrecy is usually impossible. But public health professionals pretty frequently keep some sorts of risks semi-secret, writing journal articles about them but not mentioning or barely mentioning them when talking to the public.

Here’s one example among many. The oral polio vaccine has prevented millions of polio cases. Its semi-secret side effect is that once in a while it can give a vaccinated person polio, or even get into the environment and cause a cluster of polio cases. Convinced that many parents would refuse to get their children vaccinated if they knew this semi-secret, the global polio eradication campaign routinely insisted that this known side effect couldn’t happen, even while publishing journal articles that tracked its frequency. (Unlike the oral polio vaccine, COVID-19 vaccines contain no live virus, so they truly cannot give you COVID-19.)

My clients in public health always hated it when I talked about the periodic dishonesty of their profession, when faced with what looked like an inescapable divergence between the interests of health and the interests of truth. My website is full of discussions and examples of this phenomenon. If you want to read more along these lines, you might start with my notes for a 2016 speech, entitled “U.S. Public Health Professionals Routinely Mislead the Public about Infectious Diseases: True or False? Dishonest or Self-Deceptive? Harmful or Benign?” Or if you prefer something newer, listen to the recording of my March 2021 interview with Jad Sleiman of WHYY radio, posted under the title “Public Health Messaging that Aims to Persuade the Audience at the Expense of Truth: Some Examples from COVID-19 and Earlier.”

In this column, I will settle for one piece of evidence specifically about the polio eradication campaign – an excerpt from a 2011 “Training Manual for National/Regional Supervisors and Monitors,” ![]() apparently developed for a national polio vaccination program in Yemen. The manual instructs readers: “You should memorize the following Questions and Answers.” Here is #8 in its entirety. This is what trainees were to memorize to tell any parent who asked:

apparently developed for a national polio vaccination program in Yemen. The manual instructs readers: “You should memorize the following Questions and Answers.” Here is #8 in its entirety. This is what trainees were to memorize to tell any parent who asked:

Question Are there side effects from the vaccine?

Answer

No, there are no side effects. Experience shows that if children develop diseases or symptoms after vaccination, it is a mere coincidence. They would have developed these diseases anyway, with or without vaccination.

When I wrote about OPV “misoversimplification” in 2012, the Yemen training manual was on the website of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. To the Initiative’s credit, it is no longer there – so the link above is to the Wayback Machine.

Throughout my career as a risk communication consultant, I urged a policy of what I sometimes called “radical candor” – telling uncomfortable truths even when you think you can successfully keep them secret or semi-secret. Long-term trust, I kept arguing, matters more than the short-term benefit of suppressing the bad news. I usually lost this argument. I lost it more often with public health clients than with corporate clients – probably because “good guys” get away with secrecy and semi-secrecy more often than “bad guys,” and are more readily forgiven even when their secrets get out.

As far as I can determine, in this instance public health experts and officials have been totally candid about CVST. What they’re saying to the public about the clots very closely tracks what they’re saying to each other.

2. Pause.

Candor about the clots didn’t have to mean any change in the rollouts of these two vaccines. But in the U.S. and most European countries, it did mean that. Some countries paused and then resumed using the AZ or J&J vaccine. Some countries paused and then partially resumed, no longer giving the clot-causing vaccine to the people thought most likely to experience the CVST side effect. Some countries paused and then announced they would never resume but would switch to different vaccines instead.

When I started writing this column, the U.S. was still paused. It hadn’t decided yet whether, when, or how to resume. As I was copyediting the column, the relevant advisory committee recommended resuming with no new limits on who can be vaccinated but strong new warning language about the clot risk, especially to women under 50. By the time I was ready to post, the U.S. government had accepted the recommendation.

The medical question: effect on illnesses and deaths

The most defensible rationale for pausing was to focus attention on the clot problem – the diametrical opposite of secrecy. Especially important medically was to get the attention of doctors and recent vaccinees – to teach them what clot symptoms to look for and what to do if those symptoms emerged. I think an announcement of the clot problem could have achieved these objectives without a pause, but I can’t deny that pausing added newsworthiness. I’m prepared to concede that a one- or two-day pause might have done more medical good than medical harm.

A longer pause – not to mention a permanent “pause” – seems likely to have done more medical harm than medical good. Whatever officials expected to learn during the pause they could have learned just as well without a pause (or perhaps with a pause only for women under 50). However many days they expected it to take to decide what policy changes if any the clots required, the choice was whether or not to let vaccinations proceed as before while they decided. Leave aside those places (if there are any) where pausing the AZ and J&J vaccines merely meant giving the same prospective vaccinees other vaccines instead, with zero or near-zero delay. Everywhere else, the medical question was as follows:

- If we don’t pause, X people per day will be vaccinated. How many additional CVST cases, hospitalizations, and deaths will that lead to?

- If we do pause, those same X people per day who would otherwise have been vaccinated won’t be. How many additional COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths will that lead to?

I’m a risk communication expert, not a medical expert. But I very much doubt that any medical expert would judge that in a place where COVID-19 was circulating at significant levels, the risk from the virus during the pause was smaller than the risk from the vaccine had there been no pause. Maybe young women who were being pretty careful anyway and who lived in places where the case count was low might have been better off eschewing the AZ and J&J vaccines. Maybe it even made marginal sense for officials to deny young women the choice, lest they get unwisely vaccinated. But a longish pause for all vaccinees, not just careful young women, in places with lots of COVID-19 and no ready access to an alternative vaccine, has to have done more medical harm than medical good.

The psychological question: effect on vaccine hesitancy

So if there was a rationale for pausing, especially for pausing more than a day or two, it has to have been psychological, not medical. And indeed lots of officials and experts advanced a psychological rationale: The pause, they suggested, should reassure the public that the system works – that even small signals of possible vaccine side effects are found and investigated, not ignored.

This is the “abundance of caution” argument, and it has a long history in risk perception and risk communication. It is by far the biggest question that CVST raises, and it really is in my wheelhouse. I have written about it at length: What does the public deduce from official over-caution? ![]()

There is surprisingly little empirical research on this question, a lot of it devoted to whether official precautions about mobile telephones and mobile telephone towers can mitigate public concern about cancer from the phones and towers. The answer probably depends on a variety of factors that haven’t yet been identified. But the weight of the evidence says that taking a technically unnecessary precaution in order to reassure an anxious public usually backfires. Officials hope the dominant public response will be: “Thank God they’re being so careful. I feel safer now.” The more frequent dominant public response: “If they’re being that careful, it’s probably really dangerous!”

And when the abundance of caution is relaxed, I believe the dominant response is often something along the lines of “they didn’t have courage of their convictions” or “they sold out” or “I still think it’s dangerous, where there’s smoke, there’s fire” – and far less often “they did their due diligence and decided that now it’s safe to move forward, so I feel safe moving forward too.” Again, this is mostly my impression from decades of risk communication work; there don’t seem to be a lot of actual data, though what little evidence I can find supports my impression.

The purpose of stating the “abundance of caution” rationale out loud is to increase the odds that your precaution won’t scare people. “We don’t really think this is dangerous, folks,” you’re trying to imply. Sometimes officials get more explicit, actually pointing out that they’re taking the precaution not because they are concerned but because lots of other people are concerned. The hope is that those who are concerned will feel not just reassured by the official precaution but also grateful that officials are responding to their concern. Maybe sometimes they do. Other times, undoubtedly, they feel disrespected and patronized. To the best of my knowledge, nobody has found a linguistic formula for making an official precaution sound reliably reassuring rather than alarming.

Every precaution plays this dual risk communication role. To some extent it communicates that X is dangerous; that’s why we’re taking a precaution. And to some extent it communicates that X is less dangerous now thanks to our precaution. If you’re trying to discourage the “X is dangerous” interpretation, you deploy “abundance of caution” rhetoric. If you’re trying to discourage the “X is less dangerous now” interpretation, you deploy “false sense of security” rhetoric. Neither works very well. How people interpret official precautions doesn’t seem to depend much on official rhetoric. No matter what the officials say, people usually find official precautions alarming.

I suspect most officials know that already. They didn’t often predict that pausing their vaccine rollouts while CVST was investigated would reassure the public that vaccines are safe. Instead they typically said it “should” have that effect. That’s a tell: They didn’t actually think it would. But they wished it would and they thought it should – and they hoped against hope that if they said so often enough and loudly enough, maybe it would come out that way.

Nor did officials often predict that the pause would increase vaccine hesitancy, not wanting to endorse or underline the likeliest outcome of their excessive caution. Instead, they reluctantly conceded that it “might.”

Some poll data

So did it? I think so. Some but not all recent poll data confirm that vaccine hesitancy has taken an upswing, sometimes even in countries where it had been declining. Some people who were thinking they’d probably get vaccinated pretty soon have become more tentative, choosing to wait and see what other vaccine side effects might emerge. Some who were already disinclined to get vaccinated have become more adamant, deciding they’d been right to hesitate and would now dig in their heels.

It’s hard to determine how much of this upswing in hesitancy is attributable to the clots themselves, as opposed to the pauses in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. Would the upswing have been bigger or smaller if officials had announced the discovery of the rare clotting side effect but continued the vaccine rollout without pause – as the World Health Organization and the European Medicines Agency had advised?

I think smaller. After all, one main purpose of pausing was to call attention to the clots. Officials paused the vaccination process largely in order to alert doctors and recent vaccinees to the problem. In the process, they unavoidably alerted prospective vaccinees as well, exacerbating the impact on hesitancy.

An April 15 report on an Economist/YouGov poll, for example, ran under the headline “Decision to pause Johnson & Johnson vaccine causes public confidence in vaccine to sink.” The poll was in progress when the U.S. government announced the J&J pause. Among respondents who gave their answers before the announcement, 52% considered the J&J shot “very safe” or “somewhat safe” – a number that declined to 37% among those who answered after the announcement.

An April 20 Medscape Medical News article ran under pretty much the opposite headline: “J&J Pause Did Not Upend Vaccine Confidence: Poll.” I see this as very much a glass-half-full interpretation of what seems to me a pretty discouraging poll. The key finding the article reports: “76% of 1000 registered voters surveyed nationwide said the pause didn’t decrease the likelihood that they would get vaccinated.” If 24% of the population actually became less willing to get vaccinated, that strikes me as a pretty big blow to vaccine confidence.

Three other findings of this poll:

- 61% of respondents agreed that the pause was an isolated event, while 39% picked the other option, that “this is the first of many serious side effects we will hear about.”

- 63% agreed that during the pause people should get vaccinated as soon as possible with a different vaccine, while 37% advised waiting to get vaccinated at all until more is known about the J&J clot problem.

- 53% agreed that the pause was “a good example of … rigorous safety monitoring,” while 29% said it was “a good example of why the COVID-19 vaccines are possibly unsafe, untested, and should not be taken unless you absolutely have to.” (The other 18% picked “it really doesn’t matter to me.”)

Public health professionals quoted in the article said they were “pleasantly surprised” or “encouraged” that people “are not overreacting.” It’s true the majority gave the “right” answers to these questions. But a sizable minority gave the “wrong” answers. No doubt some were simply confirmed in their preexisting determination not to get vaccinated. But it sure looks like some found the J&J pause alarming, a reason to hesitate. It was so obvious that nobody would find the pause a reason to stop hesitating that the pollsters didn’t even offer that option.

It’s complicated. An April 20 Washington Post article describes a focus group (hosted by the same people responsible for the poll I just talked about) in which vaccine-resistant Trump supporters said they were more antivax than ever, but not because of the J&J pause. In fact, one participant said “a lot of people might want to take the Johnson & Johnson vaccine versus the others, because it’s one shot versus two.” Commented one expert: “Every public health person, me included, thought this [the pause] would be a real hit to vaccine confidence. But we didn’t see folks really concerned with the pause in the J&J vaccine.”

I continue to worry that the AZ and J&J clot pauses will be a real hit to vaccine confidence. And I suspect a lot of public health professionals share my worry, whether they choose to acknowledge it or not.

U.S. media seem to have less reluctance to acknowledge the impact of the pauses on hesitancy in Europe. An April 13 New York Times article is headlined “Worry Over 2 Covid Vaccines Deals Fresh Blow to Europe’s Inoculation Push.” The article notes candidly: “There is mounting evidence that the concerns are eroding Europeans’ willingness to get the AstraZeneca vaccine in particular, and threatening to elevate already high levels of vaccine hesitancy generally.” It also reports what is perhaps the strongest evidence of increased hesitancy: multiple instances where European countries restarted AZ vaccinations after a pause to investigate the clots – and large numbers of scheduled vaccinees didn’t show up for their appointments. We shall soon see if the same thing happens in the U.S. when the J&J vaccinations resume.

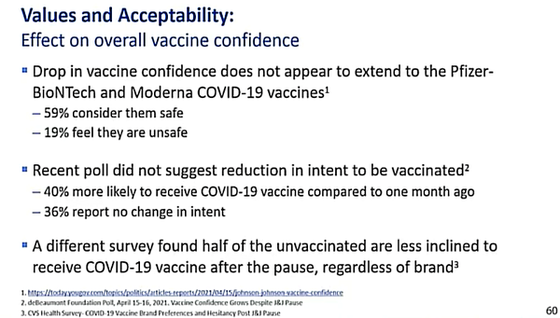

Not surprisingly, at its meeting today to decide whether to recommend resuming the J&J vaccinations, the ACIP reviewed some of the evidence on how the pause had affected U.S. vaccine hesitancy. Below is the relevant slide from the briefing they received. It’s a fairly optimistic take on the available data:

- The first bullet seems to concede in passing that there might have been a “drop in vaccine confidence,” but says that it “does not appear to extend” to the vaccines with no known clot problem.

- The second bullet says that willingness to get vaccinated is more up than down compared to a month ago, but doesn’t explicitly address the effect of the pause.

- The third bullet does address the effect of the pause, reporting a different survey that found the pause made unvaccinated people more hesitant to get vaccinated, even with the vaccines with no known clot problem.

There isn’t a bullet suggesting that the pause reassured anyone that vaccines are safer than they’d previously thought. So much for “abundance of caution.”

The built-in double message

The core paradox of the “abundance of caution” approach is that it combines taking a precaution with disclaiming that precaution. The underlying message: “We’re being more cautious than we consider necessary because you, the public, are more fearful than we consider rational. We’re not doing it because we’re concerned. We’re doing it because you’re concerned. We’re doing it to reassure you. So don’t you dare consider our precaution a reason to become more concerned.”

That paradox was rubbed in big-time when officials and experts combined the clot pauses with endless efforts to explain how tiny the clot risk really is.

In fairness, it wasn’t always the same people behind the two conflicting messages. Some academic experts and international agencies argued aggressively that pausing the vaccine rollouts was unwise precisely because the clot risk was so tiny, while national governments agreed that yes, the clot risk was tiny but announced that they were pausing their rollouts anyway in an abundance of caution. Still, the double message was vivid. Here’s how many members of the public would have tried to put the pieces together:

You say the risk of COVID-19 if we’re unvaccinated is so big that it’s horribly irresponsible for anybody to resist getting vaccinated. But you won’t let us get vaccinated with these two vaccines right now because you say the risk of the clots is too big. But you also say the risk of the clots is really, really small. And all along we’re supposed to believe you’re just following The Science.

When people are frightened of some risk the experts consider small, it’s never good risk communication to berate them for their excessive fear. This is Riskcomm 101: No matter how irrational you consider people’s concerns, respond to those concerns with empathy, not criticism and certainly never ridicule. But at least telling people they’re foolish to be worried about some tiny risk is a straightforward, honest message. Enforcing an unnecessary precaution against that tiny risk while telling them they’re foolish to be worried about it is arguably the ultimate double message.

Minimizing the potential problem / gilding the lily

The risk of CVST and related vaccine-related clots is genuinely tiny. But in their effort to reassure people that they shouldn’t take the vaccination pauses to heart, officials and experts often overstated how tiny. Over-reassurance is a cardinal sin in risk communication. It is particularly off-putting when it comes from officials who have just outlawed the very activity the safety of which they are exaggerating as they berate people for considering it dangerous.

Consider for example what is often called “the denominator problem.” In the U.S., the J&J pause resulted from finding six CVST cases among recent vaccinees, all in women under 50. (As of today, the total is up to 15, 13 of them women under 50.) At that point, 6.8 million Americans had been vaccinated with the J&J vaccine. Nearly every article used 6.8 million as the denominator and reported that the risk of CVST was six in 6.8 million – less than one in a million.

But since CVST strikes only or mostly women under 50, why include elderly men in your denominator? And since CVST symptoms take 6–13 days to show up, why include people vaccinated more recently than that in your denominator? The most honest denominator would have been the number of women under 50 who got the J&J vaccine more than six days before the pause. Estimates of that number vary, but they’re in the vicinity of one million, not 6.8 million. Six-in-a-million is still a tiny risk. But the experts and officials who said one-in-a-million – which is nearly all of them – were gilding the lily, trying to make a tiny risk sound tinier.

And think about risk comparisons. When the CVST cases were first identified in AstraZeneca vaccinees, there was a disreputable initial knee-jerk attempt to downplay the risk by emphasizing that the incidence of “clots” in people who had been vaccinated was actually lower than the incidence of “clots” in the general population. What this ignored is that not all clots are the same. The experts knew perfectly well that the sorts of CVST clots that were turning up on rare occasion in AZ vaccinees were even rarer in the general population.

Early in my career, industrial polluters sometimes used to attempt this ploy. When their emissions were proven to cause a rare kind of cancer, they would retort that the neighborhood around their factory had no more (total) cancer than the general population. They soon learned that statistical chicanery is no way to build trust.

One of the most commonly used comparisons was CVST in vaccinees versus CVST in people with COVID-19 itself. The virus causes far more CVST clots than any vaccine, we were told again and again. This risk comparison can be enlightening. But I think it’s likelier to be misleading. The implication is that if the vaccine causes fewer clots than the virus, it’s foolish to worry about vaccine clots. But the vast majority of unvaccinated people don’t get COVID-19; surely the vast majority of people unvaccinated for just a week or two during a J&J pause don’t get COVID-19. The right risk-risk comparison isn’t the risk of getting vaccinated versus the risk of getting COVID-19. It’s the risk of getting vaccinated versus the risk of not getting vaccinated and taking your chances of possibly getting COVID-19.

Another widely used comparison was birth control pills. Yes, some birth control pills cause far more clots than the AZ and J&J vaccines. And whereas for many people the vaccine alternatives are limited, there are ample birth control alternatives – less clot-inducing pills and other birth control methods. I suppose the pill comparison is meant to suggest that since we mostly accept the pill clot risk we ought to accept the vaccine clot risk too. But in that case why the pauses? A thoughtful reader learns from the comparison that the AZ and J&J vaccines are way less dangerous than many birth control pills, and then wonders why on earth our government regulators have paused the former but continue to okay the latter – a question I have yet to see answered in any article that deployed this comparison. The most parsimonious conclusion to be drawn: The regulators are entirely too irrational about risk to trust their judgment about vaccine safety.

And a piece of universal wisdom about risk comparisons ![]() : If someone is using risk comparisons to try to help you understand a risk, the natural thing to do is bracket that risk with other, more familiar risks: It’s bigger than X and smaller than Y. Anytime anyone tells you a risk is smaller than X, smaller than Y, and smaller than Z, mentioning nothing that it’s bigger than, you know they’re not trying to enlighten you – they’re trying to corner you into accepting the risk. Ditto on the other side: If all they have to say is that X, Y, and Z are all less risky than the risk you’re thinking about, they’re just trying to talk you into deciding not to take that risk.

: If someone is using risk comparisons to try to help you understand a risk, the natural thing to do is bracket that risk with other, more familiar risks: It’s bigger than X and smaller than Y. Anytime anyone tells you a risk is smaller than X, smaller than Y, and smaller than Z, mentioning nothing that it’s bigger than, you know they’re not trying to enlighten you – they’re trying to corner you into accepting the risk. Ditto on the other side: If all they have to say is that X, Y, and Z are all less risky than the risk you’re thinking about, they’re just trying to talk you into deciding not to take that risk.

Most experts and officials have been comparing the vaccine clot risk only to bigger risks, rarely to smaller ones. That’s not risk education. It’s risk propaganda.

3. Informed consent.

We are all familiar with the fact that medicines have side effects. We’ve probably scrutinized the small print on the box or bottle to see what side effects the manufacturers are required to warn us about. We’ve probably seen (but not scrutinized) the “patient package inserts” that are required to warn us in laborious detail about everything that might possibly go wrong if we take this medicine.

Similar warnings are required for vaccines. For reasons I don’t entirely understand, when you go to get vaccinated, the vaccine warnings are typically less in-your-face than the warnings attached to other medicines. Maybe it’s because you rarely get to hold a vial of vaccine in your hand the way you hold a pill bottle. Your doctor or pharmacist may or may not give you a written description of possible side effects; she may or may not ask you to sign something affirming that you’ve been properly warned; you may or may not take longer than ten seconds to look it over before you sign.

But for sure if you want to know the side effects of a vaccine, that information is available – probably from your doctor or pharmacist if you ask, certainly online from the FDA or the CDC or comparable government agencies in other countries. If you’re trying to decide whether to get vaccinated, you can certainly find official information about side effects (not to mention unofficial information, and plenty of unofficial misinformation).

That’s the informed consent protocol.

It’s not exactly a balanced protocol. Regulators don’t approve a vaccine at all unless they’re convinced that its benefits far exceed its risks. By the time they’ve approved it, they’re deeply committed to the view that the people it’s approved for really ought to get vaccinated. The vaccine manufacturers, of course, are totally onboard with this view. (Antivaxxers and vaccine skeptics are not.) So their campaigns are all about the benefits of the vaccine and the risks of going unvaccinated. They promote the benefits of the vaccine and acknowledge its risks. But they do acknowledge its risks. The information about side effects is available if you look for it.

When a vaccine or any medicine is newly approved, the available information about side effects is necessarily scanty. The required safety trials can’t find rare side effects because they don’t enroll enough people. (They also can’t find long-term side effects because they don’t last long enough.) That’s why post-marketing surveillance is required: to pick up the rare side effects that the trials missed.

With this in mind, some knowledgeable people (some doctors, for example) try to temporarily avoid new medicines, including new vaccines. If there’s an old one that’s tried-and-true and good enough, they’ll stick with the old one for a year or two while data accumulate on the new one. But of course if the new one is vastly more effective than the old one, or if there isn’t any old one, knowledgeable people take the new one. They do it knowing that the new medicine may have rare side effects nobody has identified yet. But after all, rare side effects are rare. If it’s rational to tolerate the known rare side effects of established medicines, it’s equally rational to tolerate the unknown rare side effects of new medicines.

If I were in charge, information about vaccines would include more attention to side effects. Vaccine risks would be more aggressively communicated – proclaimed, not just acknowledged. I don’t want that in order to discourage vaccination. And I don’t think it would discourage vaccination, at least not after a transition period. My goal is to get people used to the idea that vaccines do have side effects – common mild ones and, yes, rare severe ones.

And if I were in charge, information about new vaccines would include attention to unknown side effects. That too would be aggressively communicated, so prospective vaccinees would get used to it.

What I wish officials had done – way before any COVID-19 vaccines were approved or authorized: Forewarn the public much more vividly about potential post-rollout problems.

- That rare serious side effects may very well materialize after rollout,

- That officials will be candid about any such problems as soon as they’re discovered,

- That targeted changes in vaccine recommendations may be appropriate in response to these problems, and

- That as long as the problems are rare they will not interfere with the vaccine rollout.

Properly warned publics would have been less likely to overreact to rare side effects, so officials would have been under less pressure to overreact on their behalf.

The risk communication principle here is called anticipatory guidance. People who are forewarned about a problem have a chance to prepare, logistically and emotionally. They decide what steps to take now, if any, to lessen their chances of facing the problem later. And they go through vicarious rehearsal, asking themselves what they will do if they encounter it.

I would have wanted people to be told – aggressively told – that the COVID-19 vaccines were tested on tens of thousands of people and no serious side effects turned up, but when tens of millions of people have been vaccinated instead of tens of thousands, really rare, serious side effects may still turn up.

Here’s my bet: That information will not deter many people from getting vaccinated. Instead, it will help inoculate them (yes, that’s actually the term social scientists use for anticipatory guidance) against overreacting when a rare side effect does indeed turn up.

Or to put the point differently: The information that rare side effects are not a good reason to avoid getting vaccinated goes down much more smoothly when it’s learned in principle before any particular rare side effect has actually turned up. It’s a tougher sell if you tell people again and again that the trials proved the vaccines are safe, that the only side effects are mild and temporary; then a truly dangerous side effect turns up; and then you try to convince them it’s no big deal because it’s rare.

The lost opportunity for anticipatory guidance occurs endlessly in public health. The experts know that a particular undesirable event may occur. But it may not occur, and they don’t want to frighten the public unnecessarily, so they don’t mention it – or they mention it sotto voce, so only a few people actually get the message. When the bad thing happens, the rest of us are surprised because we weren’t forewarned. We’re more frightened than we would have been if we’d been forewarned. We see the risk as bigger than we would have seen it if we’d been forewarned. And then – only then – the experts belatedly try to explain that it’s not a surprise (to them), it was always on the list of things they expected might happen, so it’s no big deal.

Even so, I don’t think all was lost by the time CVST materialized as a rare side effect of the AZ and J&J vaccines. That wasn’t the optimal time to explain that discovering a rare risk the pre-authorization trials missed is no big deal. But it needn’t have been disastrous to vaccine confidence. What would I have wanted officials to say then:

- Paradoxically, it’s pretty common for rare side effects to turn up only after millions of people have been vaccinated.

- We’re sorry we didn’t do enough to alert people to this possibility in advance. We should have.

- This side effect is very serious, but it’s also very rare – too rare for us to make changes in the vaccine rollout.

- For most people, we’re pretty certain the clot risk if you’re vaccinated is lower than the COVID-19 risk if you’re not vaccinated – even if the delay is just a few weeks till you learn more about this vaccine or get access to a different vaccine.

- But the clot risk seems to be mostly to women under 50. If you’re a young woman and you can get a different vaccine instead, that makes sense. If you can’t get a different vaccine and you want to wait a week or two till we learn more about this side effect, that makes sense too, especially if you take good precautions against catching COVID-19 in the meantime.

- Above all, remember that the decision to get vaccinated or not to get vaccinated is your decision. Our advice is only advice. Your doctor’s advice is only advice. Our job is to give you not just advice but the best unbiased information we can. We hope for “informed consent.” But “informed refusal” till you learn more is your other option.

Most countries (including the U.S.) are blundering toward something like this. Doing it after a pause is a lot less effective than doing it without a pause, since the pause itself communicates risk and encourages hesitancy. But they’re getting there. Better late than never.

You could see the ACIP walking a risk communication tightrope today as it considered its options – with admirable transparency, albeit without any risk communication experts among its members. (Full disclosure: I didn’t watch. I was writing. My wife and colleague Jody Lanard watched and filled me in.) The group ended up recommending only a warning about the rare but severe risk of clots. It voted down the option of recommending that J&J vaccination no longer be offered to people under 50, or no longer to women under 50; it feared that too many of those told they couldn’t get the J&J vaccine would end up getting no vaccine, and maybe getting COVID-19 as a result. It also voted down the option of requiring vaccination sites to present the clot warning to prospective vaccinees; it feared that too many people would take such an aggressive warning too much to heart and leave without getting vaccinated.

I haven’t seen the actual language of the warning yet. I’m not even sure it’s been written yet. But even though a lot of news stories about the ACIP recommendation mentioned a “warning label,” there’s really nothing to label that prospective vaccinees would see. Apparently it’s just going to be new language added to the text of the vaccine’s Emergency Use Authorization – a government document virtually nobody sees. Given how few people will ever see the new warning, its language matters a great deal less than the language mainstream media and social media use to describe it.

Bottom line: I’m finishing this column on Friday evening, April 23, the day the ACIP met. Maybe by tomorrow, certainly by early next week, Americans will once again be able to get the J&J COVID-19 vaccine. More importantly, the word will filter out to the developing world that the United States government thinks the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is okay – okay for Americans, and so okay for anybody.

Is it too late? Are the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccines now too stigmatized to regain widespread acceptance?

My best guess – and it’s only a guess – is that rich countries are not likely to order any more doses of these two vaccines. They’ll probably succeed in finding uses for the doses they’ve already stockpiled or preordered – as domestic doses, or as donations to other countries, or both. (The government of Denmark has already announced that it will donate its doses for use in poorer countries.) But they’ll be looking for additional supplies, and probably boosters, of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines instead, vaccines that don’t seem to have the clot problem or the clot stigma.

But as I noted earlier, the AZ and J&J vaccines have huge advantages for the poorer countries – especially their lower cost and ease of storage. If these two vaccines are so stigmatized that people or governments in the developing world turn a cold shoulder to them, that could be truly disastrous … disastrous to them and insofar as the world is interconnected and pathogens know no borders, maybe disastrous to all of us.

So the big risk communication challenge to come isn’t convincing Americans and Europeans to give the AZ and J&J vaccines their informed consent. It’s convincing Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans to do so – even as Americans and Europeans look elsewhere. “Five-star vaccines for rich countries; four-star vaccines for poor countries.” Poor countries will inevitably resent this reality. Any sales pitch, especially if it comes from the rich countries, will have to acknowledge the resentment with empathy – not pretend it isn’t there or isn’t justified. But that’s a risk communication challenge for another day.

Copyright © 2021 by Peter M. Sandman