This column is about whether and how to force patients to wear masks in medical settings when you really, really want them to. With modest adjustments, it applies also to other venues (which is most venues) whose proprietors want everyone to wear a mask.

But I can’t resist prefacing my list of recommendations with a reminder that making people wear masks is a new problem. The conventional problem during disease outbreaks in the western world has typically been making people not wear masks. If you Google “masks rules” with no calendar specifications, you get article after article about required mask-wearing. Specify any period before March 2020, and you get article after article about forbidden mask-wearing.

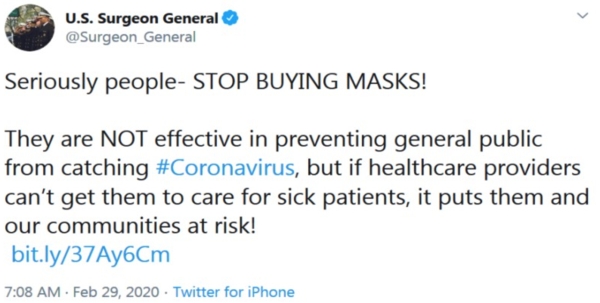

As recently as a few months ago, worried about the inadequate supply of masks and other personal protective equipment for healthcare workers, most experts and public health officials – notably including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization – aggressively insisted that for daily living mask-wearing was a useless precaution against COVID-19. The consensus was best captured by this February 29 tweet from U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams:

Seriously people – STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

Then, as evidence kept accumulating of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission, experts and officials did an about-face and began aggressively insisting that failing to wear a mask in daily living is antisocial and should be discouraged if not outlawed.

This isn’t quite as inconsistent as it sounds. The masks they really, really didn’t want us to wear (and still don’t) were medical-grade surgical masks and N95 respirators. They weren’t thinking about bandanas, scarves, and other makeshift masks unsuitable for use by healthcare providers except in extremis. And the uselessness claim was about the limited value of masks as “personal protective equipment” (PPE) to protect the wearer from getting infected by a stranger in the elevator or the grocery store. They weren’t thinking about the somewhat greater value of masks as “source control” to protect others from a wearer who doesn’t realize s/he’s infected.

So you can reconcile the two sets of claims: It’s evil to wear the sort of mask healthcare workers desperately need when you should know it won’t even protect you (much) in ordinary daily life. It’s also evil not to wear the sort of mask healthcare workers don’t want for themselves when you should know it can help protect other people (a little) in ordinary daily life.

Still, I can’t think of a more sudden reversal in public health risk communication. In what felt like a matter of days, mask-wearing went from horribly selfish to ethically and in many cases legally obligatory. And it happened with nary a “we were wrong” or even “we were unclear” or “that’s not what we meant.” It felt exactly like George Orwell’s famous (if often misquoted) line from 1984:

The past was alterable. The past never had been altered. Oceania was at war with Eastasia. Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia.

When experts and officials bothered to try to explain the about-face, their explanations were disingenuous in the extreme. Mostly they claimed that “we didn’t know until recently that asymptomatic people could spread the virus.” They could have acknowledged instead that it took them unconscionably long to grab on to the evidence of asymptomatic transmission, realize that it was a major feature of COVID-19, and accept that they would therefore have to abandon their anti-mask claims, and the sooner the better. They could have acknowledged that they had unwisely resisted this evidence as long as they could, largely by drawing functionally meaningless distinctions among “asymptomatic” (you have no symptoms and never will), “pre-symptomatic” (you have no symptoms yet), and mildly symptomatic (in hindsight you will realize you had symptoms so trivial you shrugged them off at the time). People fitting all three descriptions were unknowingly transmitting the SARS-CoV-2 virus while experts and officials continued to insist that people who felt fine should not wear masks. Convincing evidence of virus clusters launched by people who didn’t feel sick appeared in Germany in late January, then in Singapore and in France in early February, undermining official protestations in March and April that “we didn’t know until recently….”

What’s most stunning about this reversal is the long, long history of public health opposition to public mask-wearing. It’s that history, I assume, that accounts for how long it took experts and officials to reverse course.

I have written in opposition to this opposition to masks several times. I’ve written about flight attendants and even nurses forbidden to wear masks during SARS outbreaks because it might scare the customers. I’ve written about government pronouncements that wearing masks during flu outbreaks should be discouraged lest the masks give people a “false sense of security,” a possible downside the very same government documents neglect to mention when endorsing handwashing as a flu preventative.

In February 2006, concern about a possible H5N1 bird flu pandemic was rising among experts and officials, and even some of the public. Jointly with my wife and colleague Jody Lanard, I had written about why officials should stop telling people not to stockpile Tamiflu. A state health agency communication expert sent a comment to the website Guestbook suggesting that the same analysis applied to stockpiling masks. My response, again written jointly with Jody, was entitled “Surgical masks: Another pandemic risk communication controversy.” I think it’s the best thing I’ve written about masks. Here are some excerpts:

The same people who insist there’s no convincing evidence that mask-wearing by the public helps reduce the transmission of influenza also urge people to cover their mouths when they cough. Only when pressed do they concede there is not much evidence on behalf of that either. But the “experts” get to decide when they want to recommend things even though there’s no supporting evidence, and when they want to recommend against things because there’s no supporting evidence.

Not to mention that a mask does cover your mouth, and may keep you from touching your face (also widely recommended) – and it does so a lot more efficiently than a tissue or a sleeve when you’re standing on a bus holding the strap with one hand and your possessions with the other. At least until most people are wearing them, masks also increase social distance (try wearing one in public and watch the distance increase), which is universally agreed to be useful in reducing contagion….

Health officials typically offer two contradictory explanations for opposing a precaution the public finds attractive…. Both rationales are familiar with respect to surgical masks. They showed up during the SARS outbreaks and they are showing up again in debates over pandemic influenza preparedness.

- Mask-wearing will leave you too terrified to live your normal life.

- Mask-wearing will leave you too complacent to take the officially recommended precautions….

The self-efficacy that people feel when choosing which precautions to take and which to eschew helps them cope with their fears, and is thus a bulwark against panic or (more commonly) denial. That’s why offering people a menu of precautions is better risk communication than offering just one, and it’s why the precautions people come up with themselves are worth encouraging if at all possible. But none of that means that people who stockpile surgical masks (or Tamiflu) are less likely than non-stockpilers to wash their hands a lot. People who take one kind of precaution tend to take others as well. This is predictable from studies of cognitive dissonance, and demonstrable from studies of precaution-taking during the SARS outbreaks in Hong Kong and Singapore.

An unfinished mid-February draft column for this website (I have many such unfinished drafts) argued that telling people not to wear masks demonstrated “three perennial defects in the ways government officials and public health experts communicate about infectious disease outbreaks.” Here’s how I described the three defects:

- Defects of candor – not to put too fine a point on it, their messaging about masks is rife with lies, especially lies about what’s “sound science,” what’s merely plausible, and what’s their professional bias showing.

- Defects of realism – they write about masks as if everyone in their target audience went through life with both hands free, or better yet with a tissue in one hand, a trash bin in the other, and a wash basin strapped around their necks.

- Defects of empathy – they treat the human desire to do something (even if just wear a mask) to protect against a frightening new disease as if it were simultaneously foolish and selfish.

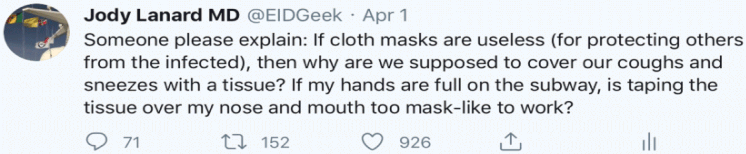

On April 1, 2020, shortly before the CDC, WHO, the Surgeon General, and the rest of the public health establishment changed their minds about masks, Jody posted a tweet that perfectly captured the foolishness of telling people to cover their coughs and sneezes with a tissue, an elbow, but for God’s Sake Not a Mask!

“Someone please explain: If cloth masks are useless (for protecting others from the infected), then why are we supposed to cover our coughs and sneezes with a tissue? If my hands are full on the subway, is taping the tissue over my nose and mouth too mask-like to work?”

So now the tables have turned. It’s no longer the people wearing masks who are being excoriated for being selfish and foolish. It’s the people not wearing masks.

That’s a huge improvement, in my judgment. The case for making people wear masks to try to reduce transmission of COVID-19 is way stronger than the case for forbidding them from doing so. Is the case strong enough to justify coercion? That’s a tougher call. It is plausible that my mask reduces your risk and your mask reduces mine, since either of us might be unknowingly infected. But the actual scientific evidence for this plausible risk reduction is pretty thin.

Still, if required mask-wearing is justifiable anywhere, it is justifiable in medical settings. People in a doctor’s office or hospital waiting room are likelier to be infected with COVID-19 than people elsewhere. They are also likelier to have fragile immune systems as a result of other medical conditions, and thus they are more at risk if they catch COVID-19. And protecting the health of healthcare providers is right at the top of COVID-19 priorities.

Not surprisingly and not unwisely, most hospitals, clinics, and individual doctors’ offices now require patients to wear masks.

This is the context for a risk communication inquiry I received a few days ago from a state health department official I often work with. It was succinctly framed: “Defiant patients refusing to wear a mask. How should solo physicians handle this?”

The pathway of the inquiry is worth noting. Several doctors in a group practice raised the issue with the practice manager. She took it to the county health department, which recommended asking the state medical board, which recommended the state health department. So the practice manager posted it on the state health department’s website. It bounced around the department for a while, and eventually got referred to the official who sent it to me.

What follows is the numbered list of points I sent back, somewhat revised after input from Jody and the state official I’d sent it to, and with changes to preserve her anonymity. As I wrote to her in my cover note, “The more useful reactions, I suspect, are toward the end of the list, starting with #6; I felt a need to clear away some underbrush first.”

The health department should prioritize healthcare worker safety over everything else – both safety from violence and safety from infection. Stand with your peeps. Say so explicitly – and explain why: If healthcare personnel are endangered, everybody’s healthcare is endangered. COVID-19 already poses that risk more vividly than any domestic disease threat in recent history.

Violence comes first. A week ago a security guard at a Walmart in Flint, Michigan was shot and killed after a dispute over the store’s mask policy. There have been other incidents around the country, and there will be more.

As a risk communication consultant, I have always told clients that safety trumps outrage management. If you are threatened, call the cops. If you feel threatened, call the cops. If one of your staff or one of your patients feels threatened, call the cops. If you think maybe you should call the cops, call the cops.

And if you can’t call the cops, or while you’re waiting for the cops to arrive, give in if you think you should: A patient who’s violently out-of-control is a much more imminent threat than a patient who isn’t wearing a mask.

I don’t know what current state law says about the obligation to wear a mask, or what various county and local ordinances say. It’s a moving target. If patients are legally required to wear a mask, the doctor’s office should do its best to enforce that requirement … but not at the risk of violence. If the law says the patient has to wear a mask and the patient refuses, I wouldn’t risk an escalation by insisting. I would politely ask the patient to wear a mask. I’d ask several times, still politely. If the patient keeps refusing but isn’t threatening, I would politely ask the patient to leave. If the patient won’t leave and won’t put on a mask, I would politely call the cops, even if the patient is not threatening violence.

But what if your local cops say they are not enforcing this law? Or if it isn’t actually a law where you are? If the cops don’t consider the mask requirement worth enforcing, there’s not much reason to call them, absent feeling threatened. I would handle an unenforced law like an in-house policy. It’s your call whether to treat a recalcitrant patient without a mask or make the patient choose between putting on a mask and leaving your office without getting treated. If mask-or-get-out is your policy, then implement it if you can do so safely. If the patient won’t leave, call the cops if you can do that safely. If that feels scary too, back off. Enforcing your mask policy isn’t worth risking deadly violence.

If there is no legal requirement for the patient to wear a mask, then there may be a legal question on the other side. Are there any circumstances under which a doctor is not entitled to require patients to wear a mask and refuse to treat patients who won’t comply? The answer may vary depending on the situation:

- When a prospective patient is asking you to become that patient’s doctor;

- When you are that patient’s doctor already and the patient is seeking routine care; and

- When the patient needs urgent care.

Before the doctor considers how s/he wants to handle these three situations, s/he should first consider whether there are any strictures imposed by law.

Also worth considering is whether medical institutions to which the doctor owes allegiance have instituted any policies that apply. Policies urging doctors to urge patients to wear masks are more or less universal. Policies vis-à-vis what doctors should do when patients refuse, on the other hand, are comparatively scarce. And the ones I’ve found are comparatively vague. Here’s one

, for example, from the Texas Medical Board. It says patients have to wear masks when they’re closer than six feet away from a medical provider or another patient. Asked whether doctors can refuse to treat patients who refuse to wear masks, it says “The decision to treat/see any patient is at the discretion of the physician/practice” – which to me implies that it’s your call whether to treat or not treat an unmasked patient. On the other hand, in answer to a different question the same document says that “If the physician chooses to deliver care and the patient cannot wear a mask, practitioners should document the circumstances surrounding the decision to render care to a patient who is not wearing a mask” – which pretty much implies that you shouldn’t treat an unmasked patient without a convincing rationale.

, for example, from the Texas Medical Board. It says patients have to wear masks when they’re closer than six feet away from a medical provider or another patient. Asked whether doctors can refuse to treat patients who refuse to wear masks, it says “The decision to treat/see any patient is at the discretion of the physician/practice” – which to me implies that it’s your call whether to treat or not treat an unmasked patient. On the other hand, in answer to a different question the same document says that “If the physician chooses to deliver care and the patient cannot wear a mask, practitioners should document the circumstances surrounding the decision to render care to a patient who is not wearing a mask” – which pretty much implies that you shouldn’t treat an unmasked patient without a convincing rationale.

Doctors should consider the actual hazard posed by an unmasked patient. This obviously depends on how much SARS-CoV-2 is currently circulating in the area; whether the unmasked patient is symptomatic (e.g. coughing or sneezing); whether there are other patients who cannot be separated from the unmasked patient; what procedures need to be performed on the patient; etc. Protecting staff and other patients from the added risk of an unmasked patient is the paramount reason for a mask policy. The magnitude of that added risk varies with the situation.

Doctors are entitled to have a mask policy that doesn’t vary with these factors. Even under conditions where you think the risk of infection is low, an unmasked patient can be a serious source of anxiety to staff and other patients. But it makes sense to think about the extent of the hazard when considering how rigidly and how aggressively to enforce the policy in a particular situation.

-

Doctors should make sure the patient knows about the mask policy in advance. Yes, anyone who’s paying the least attention should know by now that medical encounters usually require masks. (Even back in the old days a few months ago when officials were fervently anti-mask, they said masks made sense for symptomatic people going to the doctor.) But a reminder is still helpful – especially in areas where most venues are merely recommending masks while you’re flat-out requiring them. If it’s your policy to provide masks to patients who don’t bring their own, say that too.

Better yet, don’t just tell the patient your policy. Get the patient to repeat it back to you. This can be a standard part of the protocol for confirming appointments by phone or text: “I understand that I will be required to wear a mask.” It’s not just that people who have repeated the words can’t later claim they didn’t know. Repeating the words is a behavioral commitment that will help patients rein in their inclinations to resist. Alternatively, refusing to repeat the words will signal that you have a problem and a choice: continue the discussion, cancel the appointment, or make an exception.

Doctors should try to assess the patient’s reasons for refusing to wear a mask – and should consider asking the patient in a neutral, empathic way what his/her reasons are. (Preferably, this should be done in advance of the appointment, during the “reminder call,” when patients are asked to confirm their appointment and their acceptance of the mask requirement.) Of course if the patient is already threatening violence, the opportunity to respond empathically may be limited, unless someone in the office is capable of the sorts of de-escalation measures that are called for. But if it’s not too late for an empathic response, start by trying to ascertain how the situation looks to the recalcitrant patient.

One immediate clue of importance: Is the unmasked patient sitting quietly in the most distant available corner, trying to avoid endangering or frightening others? Or is s/he intentionally exacerbating the problem, sitting or standing close, shouting or coughing in other people’s faces, telling them how stupid they are to wear masks?

Here are some possible reasons a patient might refuse to wear a mask:

- The likeliest reason is outrage. Millions of Americans feel that lockdown has torn apart their lives more than the hazard posed by the virus justifies. Whether you agree or not, the grievance is profound – and it’s important (to the extent possible) to show that you understand and empathize. This is crucial to keep in mind: It very likely isn’t about the mask. It is about the patient’s feeling that policymakers have once again prioritized other people’s health concerns over his/her very survival. You may see mask-wearing as a crucial measure to reduce virus transmission, and thus as essential to resurrecting the economy. But the patient may see mask-wearing as a potent symbol of the hateful ideology that devastated the economy in the first place.

- The patient may have a real problem with masks – a kind of claustrophobia, a skin condition, etc. Even if this is unlikely, it’s a useful first question to ask, a good entrée for the patient to say “no” and then explain his or her actual reasons.

- The patient may not have any masks – forgot to bring one, ran out, can’t afford them, etc. Significant numbers of people would rather claim opposition to a requirement than acknowledge their inability to meet that requirement. I would always offer unmasked patients one of your own masks before launching into a dialogue about their “refusal.”

- The patient may have a pretty solid reason to think mask-wearing is medically unnecessary in his/her case – for example, if s/he has had a recent negative PCR test or positive serology test, or has recovered from COVID-19 already.

- The patient may see mask-wearing as a sign of weakness, and may feel a deep revulsion at publicly signaling cowardice in the face of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. (Without evidence, I suspect this is likely a big piece of President Trump’s reluctance to wear a mask.)

- The patient may be convinced that mask-wearing in general is a foolish requirement. S/he may remember that the CDC, WHO, and the vast majority of experts all said so until their recent about-face. S/he may have been told (accurately) that there is little evidence demonstrating the value of makeshift masks, and that some experts still consider them to be of negligible value or even harmful. S/he may have learned (accurately) that makeshift masks are of little value as PPE, and not be considering their possibly greater value as source control.

The most straightforward empathic response to the patient’s reasons for objecting to the mask requirement is to put yourself in listener mode. Genuinely try to find out how the situation looks to the patient.

Insofar as outrage is your diagnosis, you may want to make use of my extensive body of work on outrage management. See especially my 2010 article on “Empathic Communication in High-Stress Situations.” The most fundamental initial strategy for mitigating outrage comes in three steps:

- First let the patient vent – at length, if necessary … and if you can spare the time. Of course if the threat of violence feels imminent, it’s not safe to encourage the patient to vent. Note also that “venting” is literally hazardous with an unmasked patient; move to a separate room, stand at least six feet away, and wear a respirator.

- Then echo what the patient has told you. Don’t assume you understand. Don’t claim you understand. Ask if you understand: “Let me see if I’m hearing you right. Here’s what I heard….”

- Then find aspects of what the patient has told you that you can honestly agree with. Don’t pretend to agree with points you think are wrong, but don’t debate those points either. Focus on feelings and opinions you share.

Again, safety trumps risk communication! An imminent threat of violence may preempt any empathic response to the patient’s reasons for objecting to the mask requirement.

An alternative, counterintuitive empathic response worth considering is to get angry – not out-of-control angry, but strategically – and calmly – angry:

I’m here to keep you healthy. Everyone in this office is here to keep you healthy. In the middle of a terrifying pandemic, we are here for you. How do you think we feel when a patient cares so little about our safety that s/he won’t even wear a mask? It makes me want to scream! And how do you think a sick, fragile patient feels? This isn’t about politics. This is our office safety policy, for everyone who walks in here, including you.

A calm and strategic angry response is empathic because it’s personal and symmetrical, not patronizing, bureaucratic, abstract, or legalistic. In Martin Buber’s term, it is an “I-Thou” response. Not every patient will respond constructively – and this is too risky a strategy if the patient is already threatening violence. But in general, warm (not hot), calm anger is more empathic than cold criticism.

Just as it is helpful to assess the patient’s reasons for not wearing a mask, it is also helpful to assess your own reasons for how you choose to respond to the patient’s recalcitrance:

- Are you protecting your health and the health of your staff and other patients? That’s the best reason, of course, and it’s undoubtedly a big piece of your rationale. Now consider what else might be going on.

- Are you signaling your concern to others in the room, and trying to mitigate their health anxiety? This is a valid reason too. Staff and other patients may well become anxious – more anxious than they already are – if an unmasked patient is permitted to remain. They may become angry too, not just at the patient but also at you for failing to protect them.

- Are you irritated at the patient’s flouting of your authority? This is surely understandable – but it’s worth considering whether you would respond differently if you could put your irritation aside until later, when you can rant about it with your coworkers.

- Are you viewing the unmasked patient as a political enemy, as one of “them”? This too is understandable (although it may or may not be true). But again you may want to ask yourself if it is influencing your response more than you want it to.

Consider what accommodations may be available – and decide whether any of these accommodations is acceptable to you:

- Offer the patient a mask. (As I noted earlier, this should be automatic.)

- Offer to arrange a test for the patient and to treat him/her without a mask if s/he comes back with proof of a very recent negative PCR or positive serology test.

- Offer to put the patient in a separate room, isolated from other patients, or to reschedule the patient for a time when no other patients will be present.

- Offer the patient a face shield in lieu of a mask.

- Offer treatment by the only person on your team who’s already been infected and recovered. (This will be problematic until there is stronger evidence of post-infection immunity.)

- Offer to have everyone in contact with the patient wear N95 masks – and to bill the patient for this additional cost (if you can find a way to make that legal).

- Ask the patient to suggest accommodations that might be mutually acceptable.

The goal of offering accommodations isn’t necessarily to have the patient accept the offer. It is to demonstrate your willingness to try to find a mutually acceptable path forward. At least sometimes the patient will reject all offered accommodations … and decide to wear the damn mask.

Postscript: Masks as Virtue-Signaling

(Posted: June 7)

In the two weeks since I posted this column, I have seen more and more evidence that in the U.S. both wearing a mask and not wearing a mask have morphed into largely symbolic behaviors.

Lots of people are wearing masks over their mouths but not their noses, or even hanging down loosely from their necks. “I’m sort-of compliant,” they seem to be signaling, “but not seriously worried” – thereby staking out an intermediate position between the pro-mask and anti-mask extremists around them.

Depending on what part of the country (or even what city neighborhood) you live in, you may have become accustomed to shops posted with signs requiring customers to wear masks … or shops with “no masks allowed” signs. You may have seen groups of mask-wearing middle-aged folks berating the lone outlier who isn’t masked … or groups of mask-free teenagers mocking the lone outlier with a mask.

Some sizable percentage of both sides are virtue-signaling. They just disagree on what’s virtuous.

Others, of course, are oblivious to what they’re signaling … though they are signaling it nonetheless. Their mask-wearing decisions are grounded in how worried they are about the virus, how much risk of infection they think they face in the situation at hand, how uncomfortable they find the mask, etc.

Protest marches in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd have complicated the virtue-signaling. Much of the public health establishment quickly decided that the virtue of opposing racism in this potentially watershed moment trumped the virtue of reducing COVID-19 spread. Some 1,200 or so signed a letter asserting explicitly that “as public health advocates, we do not condemn these gatherings as risky for COVID-19 transmission. We support them as vital to the national public health and to the threatened health specifically of Black people in the United States.”

Many public health leaders tweeted their individual support as well. They mostly took the position that wearing masks and maintaining social distance were still advisable to the extent feasible, but not obligatory in a good cause. Preventing the spread of COVID-19 was reason enough to outlaw being at the bedside of one’s dying relative or praying in a church funeral for her soul, but not reason enough to criticize protest marchers in a progressive cause.

This claim isn’t necessarily hypocritical, only ideological. Public health professionals are citizens too, and as citizens they are entitled to believe that almost nothing is more important than fighting the COVID-19 pandemic – but seizing this moment to fight police racism is. (Governments, on the other hand, are not entitled to make such an ideological choice. Content neutrality is the very core of the First Amendment. Anti-racism demonstrations and anti-lockdown demonstrations – or for that matter pro-racism or pro-lockdown demonstrations – must be treated equally by every local, state, and federal government official in the United States.)

For the most part, the people pointing out that the protest marchers were often unmasked and closely packed were people who were unsympathetic to the marches, to COVID-19 precautions, or to both.

Mask science

How useful are non-medical masks against COVID-19? The evidence so far is mixed, and there’s not a lot of it. But for what it’s worth, the weight of the evidence leans toward the pro-mask side. Experts who think aerosol transmission of COVID-19 is super-important tend to dismiss mask-wearing, but they’re a minority. The majority of experts think droplets are the main means of transmission, and they tend to be pro-mask – albeit belatedly. Pretty much all experts seem to agree that insofar as bandanas and similar non-medical masks are useful in daily life, they’re useful mostly as source control (to protect others from the wearer), not as personal protective equipment (to protect the wearer from others). And pretty much all experts seem to agree that the further away you get from other people, the less it matters whether you wear a mask – and that keeping your distance is a more important precaution than mask-wearing.

Just yesterday, the World Health Organization finally joined in the near-universal claim by public health professionals that people should wear masks whenever social distancing isn’t feasible – making WHO pretty much the last major public health organization to reverse course from public health’s previous near-universal claim that nobody except caregivers, symptomatic people, and healthcare professionals should wear masks period.

In making the announcement, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was at pains to stress that “masks alone will not protect you from COVID-19” and “are not a replacement for physical distancing, hand hygiene and other public health measures.” In lieu of apologizing for having gotten the mask recommendation fatally wrong for months, he insisted that the about-face was in response to “evolving evidence” – as if the evidence hadn’t been compelling since early February that asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic people were transmitting the virus, and that masks would thus be likely to reduce transmission from people who didn’t know they were infected.

It’s pretty clear by now that masks help at least a bit, though it’s still debatable how much they help. But both sides’ disproportionate anger tells me that something is afoot besides a disagreement over the efficacy of non-medical masks against COVID-19.

Mask symbolism

After this column was posted, the health department official who originally sought my opinion sent me a follow-up email. She shared her lukewarm professional judgment that masks are probably useful, or at least not harmful. But her real passion was about the symbolic value of masks: “They’re symbols of our social contract with other people – i.e. I will do what I can do to protect those around me. And they remind us that things aren’t normal (not that we may need more reminders right now).”

Communitarianism aside, it’s patently obvious that mask-wearing has acquired partisan meaning. Plenty of people avoid masks where possible because they think their discomfort outweighs their value. But the fiercely aggressive opponents of mask-wearing are making a political statement. They see the demand that they wear masks not as a way to make it safer to come out of lockdown, but as a continuation of lockdown, a part of the same left-wing elitist conspiracy against their liberties and interests. I’m pretty sure they’re mostly Trump supporters. I am equally sure that the fiercely aggressive proponents of mask-wearing are mostly on the left, fearful of ending lockdown too quickly, and hostile to the president.

How big a role does anti-Trump animus play in the public health profession’s fervent endorsement of mask-wearing? That I don’t know. I do think experts and officials boomeranged unconvincingly from too anti-mask to too pro-mask.

I hate that the mask fight is so much about symbolism, not harm reduction. Insofar as mask supporters see masks as a symbol of the social contract (and of our president’s idiocy), opponents are entitled to give mask refusal their own symbolic meaning – as a symbol of their support for the president; of their commitment to reviving the economy; of their conviction that lockdown was a nasty, ideology-driven overreaction; of their view that healthy people shouldn’t be running scared from our inevitable and needful progress toward herd immunity; etc.

Requiring masks in doctors’ offices – the focus of my original column – still makes medical sense. There are a lot of sick people in doctors’ offices. Requiring masks in supermarkets is debatable. Requiring masks in parks and on beaches strikes me as overreach. Specifying times when masks are optional, so vulnerable people (and fervent mask supporters) can stay away during those times, would be a sensible accommodation.

I am not entitled to a professional opinion on mask efficacy. But here is my professional opinion on mask risk communication: It is very, very hard for public health experts and officials to have much credibility that masks are super-important or that going unmasked is horribly antisocial when a month ago they were on the other side just as fervently … and when their fervor seems to disappear in the face of anti-racism protest marches. It’s okay that they changed their mind about the probable value of masks. Better than okay: It’s an improvement. But maybe they should lighten up a little when lambasting those who disagree.

Copyright © 2020 by Peter M. Sandman